Harlan Ellison: Screenplays, Etc.

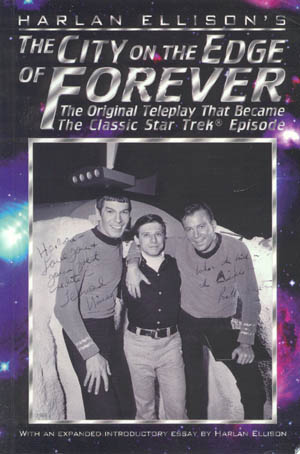

Harlan Ellison's The City on the Edge of Forever:

The Original Teleplay that Became the Classic Star Trek Episode

Review by Bill Gibron

1st Publication: White Wolf, 1996

ISBN: 1-56504-964-0

Cover and Book Design: Michael Scott Cohen

Reviews Description and Spoiler Warning

![]()

COMMENTARY

Introductory Essay

FATHER AND CHILD REUNION

“I am the greatest writer in the world. Roddenberry stinks. I worked myself into such a lather over the past thirty years that I can't even write coherently. I even threw in gratuitous profanity to prove I am really mad.” - Jim Sabo, Ultra-Condensed version of City on the Edge of Forever, The Original Screenplay, Book-a-Minute Homepage.

“Would you buy a used galaxy from this man?” - Harlan Ellison on Gene Roddenberry, 1988

Stephen King has said, on more than one occasion, that writing is like giving birth. First, there is the complicated, and somewhat mysterious period of conception and gestation. Here, ideas bloom and grow in the author’s creative womb until they have partially formed and are ready to come bursting forth. This is then followed by an intense labor, anywhere from weeks to years, in which the newborn battles and bucks, bronco-like, fighting it’s “mother” every step of the word processor until it finally relents and is born. After the rearing/editing of this literary youngster, it is set out into the world, to be judged by all who come across it. Sometimes, the assessment is harsh. Other times, there is indifference. And then there are those rare times when the work is so praised, so universally accepted, that the entire planet seems to adopt the printed child out from under the brooding relative’s eyes. It becomes part of the lexicon, the everyday speak of the masses, studied and surveyed as if divine in nature.

Thus begins the painful process of maturation and coming of age. The young work is judged against other, more established members of the fictional family, and their place in the hierarchy confirmed or denied. Individuals critique and exploit it, making names for themselves while finding faults with those they can only dream of becoming. Then there are those who will meddle, looking for ways to grab credit, even though they played no part in the “birth” of this child. Soon, there is nothing more that the parent can do, except sit back and watch as their offspring plays out its final years in the company of classics, or forgotten works. This leaves the writer with separation anxiety and the usual bitter feelings that any mother or father feels when the umbilical bond is finally severed for good.

The analogy’s truth comes from the notion that many writers feel their efforts are like children. They are remiss to find fault with them, almost always balk at controlling or restricting them, and would be hard pressed to name a favorite amongst the scholarly brood. And in the role of parent, nothing must be more painful than to see a child misrepresented, butchered by an uncaring world filled with people who only want to modify the newborn into something to serve their needs. If the “fathers” of works like The Satanic Verses or A Catcher in the Rye could have imagined what has and is being done in the name of their “children”, they may have thought twice about ever bringing them into the world. Harlan Ellison is such a parent. Almost 35 years ago, he gave birth to a simple, maudlin and beautiful boy that grew into a career chewing behemoth, haunting him, his life and his reputation to the point of emotional exhaustion and argumentative ranting. He has watched a bastard version of his son take on legendary and acclaimed status, all the while knowing that the nearly middle aged adult that exists today is a shallow, hollow and meaningless doppelganger of the nearly perfect being he created so many years ago.

The name of this child is the City on the Edge of Forever, and as Harlan enjoys proclaiming, it is consistently the best loved episode of the now religion like original Star Trek series. A simple love story, conceived around the Depression and time travel, it represents the meeting of the simplistic with the profound, a clash of destinies and ideologies, as peace has to die for the sake of war and the future of mankind. Viewed in countless reruns and Internet retellings, this is the starting point, as well as the ultimate summation, of the major Trek characters and their personalities; the philandering Kirk learning the true value of love, devotion and sacrifice; the logical and emotionally devoid Spock recognizing his human half side, and the suffering of his captain and friend; the pain and torment of Dr. McCoy as he wrestles himself inside a body filled with lethal drugs, his scientific mind clouded by waves of paranoia and hysteria. When the final act has played itself out, and the balance of time and space has been set right, one is left drained, stunned by the story told, moved by the cruel way fate deals it’s stacked deck, and knowing that the characters we would soon grow to love would never be the same again. It was, and still is, a benchmark in the creation of the Trek legend.

Still, with all its power and glory, this wee barren has not made his pater proud at all. After years of fielding questions, awards and accusations, Ellison has decided to combat the juggernaut phalanxed around his progeny and set the record straight, more or less. As straight, that is, as an irate and angry parent can be. Harlan Ellison’s The City on the Edge of Forever: The Original Teleplay That Became the Classic Star Trek Episode is a final act of vengeance, a kiss off to everyone who ever mistreated, misspoke of, or mischaracterized his work. Undoubtedly one of the most prolific and skilled writers of the last 50 years, Ellison has compiled a staggering body of work. Thousands of stories, hundreds of books and screenplays, countless non-fiction essays and personal op-eds have graced magazines, bookshelves and screens both big and small. Yet Ellison is not ready to sit back and collect his accolades. Seeing his baby, the child of his creativity and authorship suddenly become the slave-like dominion in the ever-growing cult of Roddenberry, to be enveloped into a world of lying, scheming and credit hogging sickens Harlan. And when he is ill, he has no problem expelling his bile on even this most legendary of Trek episodes.

For you see, there is legend and then there is fact. And Ellison loves to harp on the facts. Factually, the story he wrote never made it fully to the screen. Sure, the majority of it is there; the plot, the important characters, the emotional and philosophical issues. But Ellison views the televised version as a respectable fraud, one based in his work but not of his work. Harlan has always believed in the Writer as God, the source of all inspiration, characterization and dramatization. Nothing is more important to him than the word; actors, directors, vision and budgets be damned. It is the writer’s work, the creative spark, to which they all owe the glowing warmth of praise and gratitude. Yet, in the case of City commendation is the last light that has ever shimmered from the keepers of Starfleet’s flame. He has been accused of being everything and everyone, from a two-faced moneygrubber to an insensitive and spiteful lout, all for not worshipping at the church of Kirk. And the wrath he has personally had to face at trying to defend himself has now been channeled back into a pinpoint laser of rage, a fierce introductory essay taking aim at the mythology and folklore of City’s birth.

To understand Ellison’s anger, one needs look no further than the numerous untrue stories that have floated around about this script. Almost as popular and lasting as the episode itself, these fables have been repeated to the point where they are better known and more vital to the ongoing saga of the show than the scripts themselves. First and foremost is this notion of Scotty dealing drugs on the Enterprise. For years, in almost any interview he gave, Gene Roddenberry had a set mantra about Ellison, City and the subsequent disputes.

“He had Scotty dealing drugs!”

It was a quick and easy answer, the automatic response to anyone who dared question the viability of Ellison’s version. Roddenberry would then go on to repeat the other major pieces of Trek party line propaganda:

“The script was too expensive, and basically un-filmable”.

“It was rewritten so many times that there is not much left of Ellison’s original.”

For years, after all the awards and accolades, the threats and the compromises, the great man of the universe still boldly dared go where other men had gone, basically, to the actual story.

And had truth actually been told, the mighty Gene would have toppled from his Ivory pedestal and found himself floundering amongst the legion of defeated dramatists who sacrificed their talent, reputation and credibility in service of his overly optimistic view of the future. Having never met an idea he didn t take credit for, he spent his life in the active defamation of people like Ellison, writers and creative artists who, while breathing life into his usually tired scenarios, found themselves on the outside barely looking in when it came time to award recognition. Roddenberry was, and is, no saint when it comes to City. He welcomed the confrontations and delighted in the misinformation, as it bolstered his agenda while leaving people like HE looking trivial and disturbed. Make no mistake, when the father of the Starship Enterprise wanted something his way, no code of ethics, morality or propriety was safe. He butchered City to serve his own needs, and lied consistently to the media to make the story stick.

It is in these repeated falsehoods that Ellison's anger lies and relishes, mostly to his own bitter detriment. While the beautiful script speaks for itself (both pro AND con), Harlan rants and curses, page after page, about how Roddenberry lied. He lied about Scotty. He lied about the drugs. He lied about the cost and the special effects issues. Doing more research and interviewing than most journalists in pursuit of the details, he cites article, after interview after personal recollection in defense of his version, a version clearly seen on the page. Time and time again, when an interesting story or an artistic insight would serve his point better, Harlan hurls his profanity-laced barbs and regurgitates his “proof”. Armed only with these salient facts, Ellison offers little other insights into the writing or creation process. His introduction is meant, in 25,000 words, to right the decades of wrong inspired in the Star Trek hegemony. And he has every right to do so. His essay effort is, however, a little like taking on the New Testament of The Bible with the argument “Jesus never lived’ and having all the physical proof to back up your story. No matter how many times you say it, the public entrenchment is so complete that no amount of revision will reverse it.

Eventually, the argument loses steam. By the fifth “Scotty is not even in the @#&*@ script”, one has grown tirade tired and longs for something more than the anger pouring forth. Does Ellison have a right to be angry? Certainly. But his points become spurious when all he can do is repeat them. He acknowledges the repetition, but does not apologize for it. Mind you, Roddenberry is not the sole target for his ire-laced exercise in revisionist history. He has many other, less than stellar, bones to pick clean, longtime informational sources more worthy of ridicule than retraction. Taking such intellectual luminaries as Joan Collins and William Shatner to task for the consistent putting of foot into mouth that they do in recalling their days on Trek and the City episode is a bit like taking a dog to task for not being able to tie its shoes. Still, we are treated to page after page of the great one, this literary giant, stooping to conquer the peons that, for so long, have treated his baby poorly, badly and disrespectfully. If only all parents were this unhinged about caring for their flesh children.

In the end, one can only glean minor pearls of noteworthy information from the parched and barren fields left in HE’s slash and burn brand of retribution. The primary idea that one walks away with is that, when faced with the “legend” and the facts, there is no other side for argument than Ellison’s. Clearly, the truth has set his version free. But we learn precious little of the why? There are so few conclusions drawn as to why the changes were made, that in the end, it seems that Roddenberry and his crew had to be, either, the stupidest producers a show has ever had, or the most cunningly evil. These are the only conclusions one can rationally draw when viewed in light of the fact that Gene Roddenberry screwed the very man he begged to help him save his floundering Star Trek. That’s right, Ellison was instrumental in forming and working with The Committee, a who’s who of famous authors, which spearheaded the nationwide letter writing campaign that brought the Enterprise back from the dead. Still, we do get a pseudo walk through of the writer’s process, a journey of treatments, scripts, re-writes and afterwards. It is perhaps, in these final pages, where the true story of the City on the Edge of Forever finds its final resting home.

In the words of David Gerrold:

“You are your word. Harlan Ellison understands this: I’m not sure that Gene Roddenberry ever did; but the difference between speaking a commitment and living it is the difference between eating the menu and eating the meal.”

It is safe to say that, after this introduction, Ellison is very, very full.

Treatment: 21 March 1966

The classic outlined. We are introduced to Beckwith, a rogue Enterprise crewmember, the Jewels of Sound (a kind of ‘dream narcotic’) and the illegal smuggling trade going on. Beckwith kills LeBeque, another crewmember and is court-martialed. He is sentenced to exile on an abandoned planet. Finding an isolated, gray block of a world, the Enterprise officers beam down to investigate further, and to carry out Beckwith’s punishment. They come across the Guardians of Time, ancient entities whose purpose is to guard and control the flow of time. Kirk is curious, and asks to see how. The Guardians oblige, and show glimpses of the past through their time machine. Kirk asks if the past can be changed, and the Guardians assure him it can be.

Just then, Beckwith breaks free of his captures and vanishes into the time machine. The Guardians announce that the world as the crew of the Enterprise knew it, has changed. They offer no more information and disappear. Kirk and crew return to the Enterprise, only to find it infested with cutthroat space pirates. Returning to the planet, the Guardians offer to send Kirk and Spock back to approximately where Beckwith went. They cannot go back to the exact time, however. The Guardians, indicate that Edith Koestler is the link between Beckwith, time and the fate of the Enterprise. Kirk and Spock enter the time machine. They arrive one week before Beckwith, in Chicago, 1930.

The arrival of such alien beings to old earth startles an apple cart vendor, who dies of a heart attack. Kirk and Spock must make their escape. Hiding in the basement of a kindly old man, they are given menial work and attempt to fit in. Meanwhile, the Enterprise crew faces the wrath of the space pirates. Eventually, Kirk meets Edith, and they begin to fall in love. Spock plans to intercept Beckwith when he arrives, but the assassination plan fails. As the time moves closer to the day, Spock sees the love growing in Kirk. The Guardians said that Edith must die, but Kirk cannot imagine it.

Finally, the setup occurs. Edith is crossing the street to Kirk as the truck destined to kill her rounds the bend. Beckwith moves to save Edith, and Kirk stands motionless, unable to prevent Beckwith’s act. Spock intercedes and the truck kills Edith. Kirk is devastated. They return to the Guardians, Beckwith in tow. They are told the world is back to normal. They request a punishment for Beckwith, and return to the Enterprise. The Guardians grant Kirk’s wish and place Beckwith in a mobieus loop of time, constantly entering and dying in the center of the sun. Later, Kirk and Spock meet in the Captain’s quarters. Spock calls Kirk “Jim” in an attempt to show compassion.

It’s a good story, but, surprisingly, there are some weak elements. The pirates seem completely out of place, and the whole notion of the romance is dealt with in generalities, nothing specific as to why a Starfleet captain would risk time and space for it. Also, the link between Edith and the future is never developed. She is simply “pointed out” by the Guardians, but why she is important is not detailed. Now, this is a treatment but one would expect some notion as to why the life of this simple girl is so important that it would alter the future.

Treatment: 3 May 1966

Same story with some modified/additional elements. Beckwith is not court-martialed, but escapes to the Guardian planet after the murder. There is a scene that describes the crew watching the Time Machine scale through the eons. Beckwith comes out from hiding and leaps through the machine as it is set on Chicago, 1930. The Guardians give omens as to who the vital time center is. The pirates are still there, and the notion of Spock and Kirk going back. They meet up with Edith Keeler (note the name change) and the events tend to play out the way they did before. One interesting scene shows Kirk failing to stop Edith from falling down a flight of stairs, hinting that he understands that she must die, but in his reaction we see that this is an isolated event, and when the real time comes Kirk cannot act. The story plays out as before. The improvements add some insight, but Keeler is still an enigma. No clue as to why she is crucial to the future.

Teleplay: June 1966

First, let’s point out the differences from the treatments. The pirates are now called RENEGADES. The Tri-corder becomes more important. It is this electronic translator that tells Kirk and Spock that Edith will die, not the Guardians. And we meet Trooper, a veteran of WWI who first finds, then is killed by, Beckwith. Edith is seen as a woman with hilosophies ahead of her time, but nothing specific to give her the weight of the fate of the universe. She dies. Everything is set right. Beckwith ends up in the sun, and Spock calls Kirk “Jim”.

It is a wonderful script, full of the florid writing and clever plotting that marks Ellison’s work. But the inherent flaws become far more obvious when viewed in light of the televised episode. Harlan wants to focus on love, on how the hard and resentful Kirk melts in the arms of the forward thinking Edith. All the other plot points serve this main story. We must see if Kirk will sacrifice his heart for Edith’s life. But, aside from some ideological maturity, Edith is given no import in the manner of the world. She is the key to an entire space-time shift, but her importance in the grand scheme of things is never revealed. Sure, Spock hints at some possible reasons, but there is nothing concrete. No matter what Ellison thinks, this is a logic flaw that interferes with the drama. If someone told you the accidental death of your maiden aunt would alter time and space, you would want to know something more about her. Here, we are told she is nice and clever and intelligent, and that is just not enough to engage the reader or make us care about her fate.

Ellison also writes, in his introduction, about his love for a character called Trooper and how hurt he was to see him go. Well, maybe Trooper reminds Ellison of someone from his personal past, but his role here is ornamental and manipulative, to make us pity a poor street person just to mourn his death at the hands of amoral Beckwith. Trooper adds no important dynamic to the story. He is exploitation, a red herring for us to be saddened over as we wait for Edith’s fate. Still, one cannot fault Ellison’s overall plot. It is brilliant in conception, and engages us as all tales of time travel do. The comic scenes of Spock and Kirk work quite well, as do the more menacing aspects of the fish out of water scenario. Spock is the main focus here, and it is clear why some of the show contributors would have a problem with this; Kirk is not a strong, resourceful captain, and the logical alien ends up doing it all, from answering questions, to righting the wrongs, to comforting the emotionally damaged. How this meshes with the Spock we have since come to know from the series may offer a glimpse as to why, in Roddenberry’s words, the script was unfilmable.

Ellison does have a very vivid and visual idea for the piece, something that 1960’s technology could only have hoped to recreate. Heck, some of effects he envisions would have been costly up to a few years ago, before the computer could make convincing dinosaurs walk among humans. The Time Machine, the Jewels of Sound, the Guardians and even the Chicago locales would be out of reach for a show that could barely keep the main deck doors from slamming into the actors. Basically, just like Edith Keeler, this script was before its time. It was before the Enterprise and its characters had been established. It was before science caught up with imagination. It was before television was willing to grant, without a proven record of financial success or a hit show, complete creative control to a young, talented writer. One could easily imagine it being filmed today, as an experiment, to see how it stands up to the aired episode. In some ways, this is a better reading, than viewing, experience. Perhaps this book is the proper format for it, after all.

Second Revised Draft: 1 December 1966

A bizarre development. In an obvious response to the “drug dealing” story line, Ellison offers another scenario to get us onto the Guardian’s planet. McCoy is examining an alien beast when the Enterprise is violently thrown by a radiation surge. McCoy lands on the little animal that bites his hand. McCoy goes insane with alien ‘poison’ and escapes to the Guardian planet surface. Spock indicates that he will be dead in two hours if not saved. The Guardians are no longer beings, but pure energy (obviously to “save money” on actors and effects). Still, McCoy rambles through the time portal, and the rest of the script remains intact, with McCoy in the Beckwith role.

Afterwords

As stated before, Ellison went to great lengths to get the insights and opinions of those closest to the making of Trek and the episode in question. After his work, he gives space over to these writers, actors and executives to plead their case/cause/musings. Some are interesting, almost all self-serving. Of the contributions, only Peter David and D.C. Fontana attempt to balance the facts via Ellison with the impact of his story, and the notion of Roddenberry’s control and mythology. Sure, the teleplay is better. But it is not the teleplay that consistently wins fan and audience polls. If Ellison’s work is a bastard, than all members of the biological primordial ooze should get some credit, as they all helped to created the dramatic DNA which gives City its staying power. All others seem content to call Ellison a genius. (Like there needs to be a whole section to establish that point)

Peter David

Admits to hating the script, and then having an epiphany, years later, as

to its greatness. He mentions Richard Arnold, keeper of the Trek Commandments,

and lets Arnold’s bitter recollections of Ellison speak for Roddenberry. In

the end, Harlan is great, the Trek monolith is bad.

D.C.Fontana

Admits to working on the televised script. Does a good job of analyzing

the “flaws” in Harlan’s original, pointing out things that would not work

in a series television format. Still, in the end of her story, she comes to

praise the original. (A work, by the way, she was more than happy to rewrite

at Roddenberry’s behest)

David Gerrold

I have come to praise Ellison. The end.

DeForest Kelley

A nice anecdote about seeing Ellison in the commissary during the Trek

days. Goes on to say what a great script it really is. Really.

Walter Koenig

Had a big fight with Ellison in 1984. Swore he would never speak to him

again. Changed his mind. Thinks the script is just wonderful.

Leonard Nimoy

Loves Harlan and all he stands for.

Melinda M. Snodgrass

Discusses how she too got screwed by the Roddenberry machine when working

on Star Trek: The Next Generation. So she sympathizes with Ellison.

She has been there.

George Takei

Liked the televised episode a lot. Thought, “What’s the big deal?” about the

original. Read the script. Now thinks it’s greater.

Conclusion

As their entire career as a group was trickling to its unspectacular end, John Lennon and Paul McCartney playfully harmonized on one noble thought:

“And in the end, the love you take, is equal to the love you make.”

In the wake of the Introductory Essay, with all its acrid jibes and data repetition, it is clear that there is no love lost, to make or take between Ellison, Star Trek and its now dead founder. And that’s a shame. For decades now, fans have loved the child fathered by Ellison, nurtured and (most would say) neutered by Roddenberry, and adopted by the dedicated throng as a living testament to the power of both minds. So what if Doctor McCoy’s accidental injection of drugs is as stupid as Ellison sees it. Millions of fans don’t seem to care. Who cares that the gentle nature of Edith Keeler now seems tarnished by the shadow of Nazism and the notion that her life would have lead to a victory for the Axis power. The love story remains, full of the passion and pathos that Ellison worked so hard to achieve. And what of Trooper, lying on the cutting room floor, along with Beckwith and the Jewels of Sound? In reality, they are not missed. They can be enjoyed in the script for what they are, but viewed in the harsh light of Star Trek, what we know about the characters and the crew of the Enterprise, their existence may seem reasonable but not essential. In some ways, they detract from the message the original series wanted to portray, a value that Ellison scoffs at as goody-goody and pie in the sky.

Still, no matter what the critical opinion, the fans vote with their heart, and they seem to like the altered, under baked version of City. Would they like the episode had they used the original script? Maybe. One will never know. But they truly love this one. And in this end, the love they have shown for Harlan and his work should more than make up for the years of pain he had to suffer at the hands of Roddenberry and the other bearers of the Star Trek mythos torch. He can curse and swear and hate all he wants, but the one fact will always remain; when combined together, the good and the bad, something lasting and magical occurred. And immortality is something that any father can only dream of for his child. And vice versa.

Review by Bill Gibron (bgibron@tampabay.rr.com)